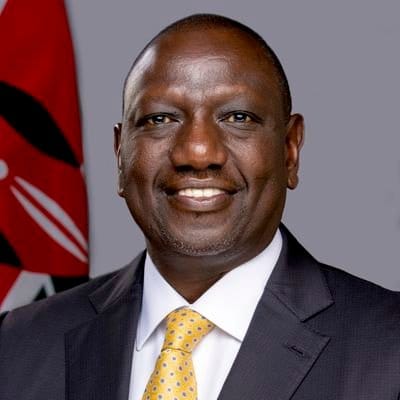

Kenya’s leadership, under President William Ruto, frequently references Singapore as a model for rapid development, promoting the vision of turning Kenya into the “Singapore of Africa.” The President’s push comes amid calls for ambitious infrastructure projects, backed by the National Infrastructure Fund and the Sovereign Wealth Fund, aimed at modernizing the country and driving economic growth.

Singapore’s journey from a resource-poor, multi-ethnic island to a global economic powerhouse offers key lessons. Following independence in 1965, Singapore faced severe challenges: a lack of natural resources, poor infrastructure, high unemployment, and a volatile regional environment. Its leaders, particularly founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, implemented visionary policies emphasizing strict governance, anti-corruption measures, business-friendly laws, merit-based systems, education, and infrastructure development. By focusing on human capital, strategic industrialization, and social cohesion, Singapore transformed itself into a thriving export-oriented economy with world-class infrastructure, education, and a strong business environment.

In contrast, Kenya has faced persistent challenges since independence, including corruption, political instability, weak institutions, and inconsistent economic policies. These factors have limited growth, eroded public trust, and undermined service delivery. While Kenya is resource-rich and demographically young, development has been slowed by mismanagement, ethnic politics, and misplaced priorities, leaving critical sectors such as healthcare, manufacturing, and education underdeveloped.

President Ruto’s vision seeks to address these gaps by drawing lessons from Singapore: implementing long-term, strategic planning, strengthening institutions, promoting social cohesion, improving infrastructure, and investing in human capital. His administration argues that with disciplined leadership, transparency, and targeted investments, Kenya could emulate aspects of Singapore’s success, particularly in logistics, trade, education, and technology.

Critics caution that Kenya’s path is more complex, given its larger population, geographic size, and entrenched governance challenges. However, proponents of the plan argue that focused, pragmatic leadership, consistent policies, and investments in people and infrastructure could gradually close the gap.

Ruto emphasizes that Kenya’s transformation requires eliminating corruption, ethnic and political divisions, and prioritizing development projects that create jobs, build infrastructure, and strengthen institutions. While replicating Singapore’s exact trajectory may be ambitious, the blueprint serves as a strategic guide for Kenya to pursue sustainable economic growth and regional competitiveness.

In essence, the President’s Singapore-inspired vision underscores the importance of disciplined governance, long-term planning, and human capital development as Kenya charts its path toward becoming a globally competitive economy.